Aleh Hruzdzilovich: I wrote about abuse. I went through prison. And I proved that freedom cannot be crushed

This interview is part of the collection “Voice of the Freedom Generation”, a living testimony to the creative and civic presence of those who have not lost their voice even in exile.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich in the Seimas of Lithuania. December 1, 2022. Photo: BAJ

The collection tells the story of the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award, founded by the Belarusian PEN in partnership with the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, Press Club Belarus and Free Press for Eastern Europe endowment fund. The collection will be presented on November 15, 2025 at 5:00 PM during a discussion with the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award at the European Solidarity Center (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, Gdańsk, pl. Solidarności 1).

Brest was the only city in the Russian Empire that was utterly destroyed and rebuilt from the ground up, all because of the fortress

Aleh, do you believe in destiny as written in the stars? Have you ever been interested in astrology?

In my case, the geography and location are more significant than the geometry of the skies. I don’t know who I would have become if I had lived in Homel or Mahilou. My hometown is Maladzechna, which was once a regional center. At that time, the Khrushchev administration was in power, and the region was liquidated. My parents faced the choice of moving somewhere else because their jobs were gone. My dad even went to Hrodna to try it out, and he found that everything was fine there, except for career prospects. In Brest, he was offered a position as deputy head of the local industry department. His qualifications were suitable, and he was also promised a rent-free apartment. As you say, the planets aligned. The choice was made, and my fate was sealed.

Were you and your twin brother born in the centrally located residence for government officials?

Far from it! First, we rented an apartment in a wooden house on the outskirts of the city. It’s a stereotype that bosses in the Soviet system were all stocked. My mother didn’t have enough milk for us, but luckily, a woman who sold goat milk lived nearby. We grew up on it. Much later, my father began receiving nomenclature gifts twice a year: a bundle of fish, a stick of sausage, a pack of buckwheat, some biscuits, and a small tin of instant coffee. That was it. The privileges enjoyed by the local party bureaucracy at that time are essentially a myth.

How did living in Brest, a city on the border, affect your worldview and life?

“Gateway to Europe” may sound trite, but it certainly had an impact. For example, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones became popular in our city when most young people in the USSR hadn’t even heard of them. It was the other way around with Vysotsky.[1]

Secondly, the city of military glory played a vital role in education.

The third factor was my father’s successful career. He started as head of the Department of Local Industry. He quickly became the deputy chairman of the City Executive Committee and, in 1968, the chairman — a position akin to present-day mayor. Although “mayor’s offices” are largely powerless even now, let alone back then. He was in charge for ten years.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich at work. 1996. Photo: from his own archive

The entire country of Belarus experienced significant socio-economic advancement. Industry tugged the whole of urban infrastructure along with it. Even a schoolchild could notice the pace of urbanization.

The time was really unique. But I observed this not through the factories and plants, but through the Brest Fortress, which had just been awarded the Hero Star. Large-scale reconstruction of the ruins has begun. I witnessed conversations and arguments with the legendary sculptor, Aliaksandr Kibalnikau. My father told me about his meetings with Sergey Smirnov, a publicist and the author of a book about the exploits of the citadel’s defenders.

Did he mention General Krivoshein? He and the German tank commander, Guderian, took part in the 1939 parade in Brest.

Yes, I have an interesting mention to share. In the 1980s, Znamya Yunosti journalists attended a meeting of veterans who vehemently disagreed with our article about these events. “It’s lies! A commissioned publication!” I stood up: “My father personally met with Krivoshein, and I saw the photo of that parade myself. This is history. With all due respect, your perspectives are myths. On September 22, 1939, a Soviet-German military parade was held in Brest to celebrate the transfer of the city and fortress into our control. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in action.”

I suppose there wasn’t any applause for that enlightenment.

No, they made a lot of noise and booing. And one officer, wearing colonel’s epaulettes, exclaimed: “Ah, well, it’s clear: Hruzdzilovich is a Jew.” By the way, I observed that there were quite a few anti-Semites among the zealous communists.

And how did the young man from the nomenklatura family become interested in promoting Belarusianness?

I actually studied at an elite special school. I studied English, geography, technical translation, and literature. The teachers were highly educated. The physics teacher introduced us to The Master and Margarita, and the English teacher discussed her meetings with young people who spoke Belarusian and criticized the “renovation” of the fortress. They said, “It needs preservation, not renovation.” In fact, this was the only city in the Russian Empire that was utterly destroyed and rebuilt from the ground up — all because of the fortress. Right next to it. The teacher was particularly interested in the young journalists who uncovered these facts.

Of course, there was an abundance of scientific communism, although I was already a semi-finished product of propaganda

So did the cold shower, the counter-truth to what had fueled patriotic fervor, unexpectedly spark your interest in journalism?

One could say that. But it started with something else. I grew up with the mindset of a sincere communist. I was concerned about the spread of socialism worldwide. I was a schoolboy when the Salazar regime was overthrown in Portugal, and I was stunned by the news. I began to follow the events. Moreover, the central press wrote interestingly and extensively about it. This is what inspired my desire to become a journalist. I started collaborating with the regional Zarya newspaper in the ninth grade, established contacts, and wrote articles.

They probably edited your text mercilessly. Did the red ink not dampen your enthusiasm? When did a text appear that you could genuinely be proud of, instead of just another routine note?

I took editing in stride. I thought it was essential to write an article about what modern schools lacked. With some help, I attempted to write a real analytical article. An older friend of mine, a well-known Brest-based activist, advised me and cleaned up the text. He shared a legendary surname with Anatoly Agranovsky, the star of Soviet journalism from Moscow. At the time, I didn’t know this, so I wrote in my creative essay: “Agranovsky was my ideological teacher.” The dean of the journalism department, Ryhor Bulatski, launched a barrage of accusations. Like I brazenly took credit for knowing the master! This is how I became interested in Anatoly Agranovsky’s work.

After reading his books of essays and reflections on journalism, were your teachers no longer impressive? The department focused more on forging ideologues than on the essence of the profession.

Of course, there was an abundance of scientific communism, although I was already a semi-finished product of propaganda. But they also taught the craft, including genre theory, layout, and photography. In general, any university education is broader than a profession. Not only what is being taught, but also who is around matters. People, contacts, and atmosphere all matter. For instance, we had the opportunity to meet with Vasil Bykau[2] in the second year. I remember how modestly this famous man behaved and how carefully he chose his words. Then came the contrast: a meeting with radio journalist Nina Chaika — just nothing burger. As the saying goes, feel the difference.

During Perestroika, Belarus became one of the “mouthpieces of the Vendée.” As a propaganda school, the journalism faculty did not lose its case. However, editorial ideologues were typically weak professionals. Have you noticed this?

Yes, editors should avoid slogan-based rhetoric because it stifles creativity. I felt it intuitively. For example, after I graduated, the editor-in-chief of Zarya, Piotr Sutko, invited me to join his team, but I refused for ideological reasons. My father was a boss; they would see me as his shadow, try to use me as their agent among the city power figures, to push me into the official circles. That’s why I chose Integral, a neutral, working-class weekly from Minsk. A year later, I accepted an offer to become an instructor in the propaganda department of the regional Komsomol committee. I was promised an apartment. There was a 20-year waiting list for factory worker housing, but I had a family: a wife, a son. I had to find a solution.

It made perfect sense for you to start in the first roles within the propaganda stable and build a career as a party member. Or could you already feel that it wasn’t your cup of tea?

On the contrary, it was there that I lost all of my former communist illusions. I grew closer to my peers during business trips. In the evenings, after the Komsomol rhetoric ended and the music began, another talk started. “You don’t know life! Everything works differently than it does in theory.” They would then shower me with facts.

They once sent me to work at the Moscow Youth Festival. While the Komsomol leaders in Belarus still had some sense of shame, in Russia, it was sheer horror. They filched everything they could. The head of our group — a secretary of the regional committee somewhere in Ryazan or Bryansk — was a plain thief. He pinched everything within reach.

I recall working on the railroad during my student days. The foreman would sneak something in there, too. One day, I saw him stashing a rope. “Why do you need it?” I ask. “Well, my dog won’t let me come home unless I bring something,” he replies. A lively joke rooted in reality. They had the same mindset: you had to pinch something. Stickers, receipts, gas coupons, food stamps — everything was tapped into.

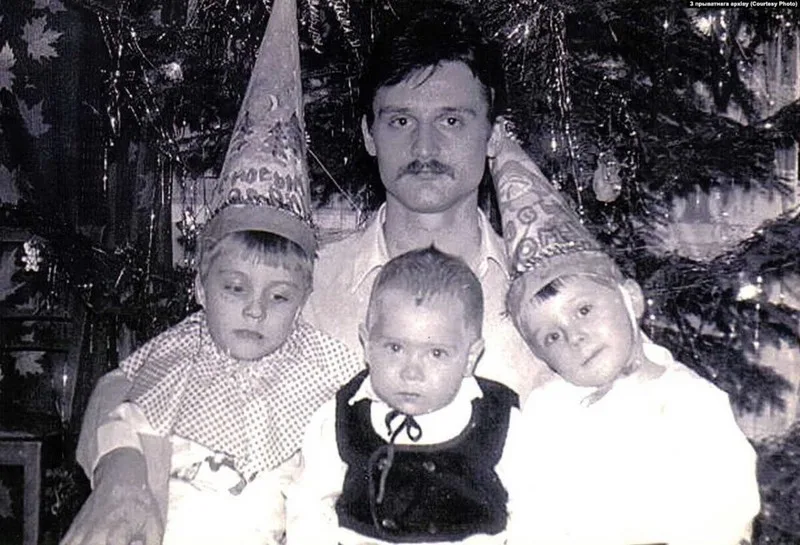

Aleh Hruzdzilovich with his children. Photo from personal archive

And you were sent to investigate something you no longer believed in?

Let’s say I was going to review the lecture groups’ work. It was a complete fiction. Nothing was implemented, just on paper. You could criticize the Komsomol secretary, but consider his circumstances: his child was sick and his life was stuck. And here you came with your party line and the discussion of the next congress. And you saw it’s all just a performance. So gradually, I became disillusioned with the system.

I remember Brezhnev dying. My task was to “write a telegram of condolences from the region’s youth.” So I wrote, “We deeply grieve,” “May the leader’s memory be bright,” and “Great son of the party.” I don’t know why I didn’t throw the draft away. I put it in a drawer.

A year later, Andropov dies. They call again: “We need a telegram.” I take out the old one, clean it up, and take it to the boss. They are full of admiration: “Well done, promptly!” Chernenko died a year and a half later. I am being ironic, “Wait, just five minutes!” Everyone laughs as if it’s normal.

The boss arrives: “Well done! This is the Komsomol of the new era!” So I shifted from being a culprit to a hero

The life span of the system was determined by its conventionality. Were you ready for perestroika?

I was employed as an executive secretary at Znamya Yunosti at the time. The newspaper was booming, keeping up with the times. It had a free editorial policy and journalists who had a way with words. And suddenly, in 1988, Nina Andreyeva sent her article, “I can’t compromise my principles.” At that time, Aliaksandr Salamakha was the head of the newspaper. One evening, before leaving, he threw the typed proofs on my table. “Put these in for the Saturday issue.” I read it and realized they’re using us to spread practically Black-Hundred-style[3] slander — the newspaper has the largest circulation in Belarus, over half a million.

I gathered my colleagues: Yury Veltner, Larysa Sayenka, Pavel Uladzimirau, and others. The discussion was intense, but the majority decided against publishing it.

The following Monday, there was a debriefing. An instructor from the Central Committee, Mr Krukouski, rushed into the office, and they began summoning people one by one, pressing: “Why wasn’t it published? You’ve violated party discipline!” Young journalists were threatened with dismissal. They didn’t pressure me much. However, before leaving, Krukouski angrily whispered, “I’ll destroy you!”

However, a surprising reversal took place just two days later. Aleksandr Yakovlev, a member of the Politburo, spoke in Moscow, calling that article an “anti-perestroika manifesto.” It turned out that Gorbachev himself considered it a diversion. He even said in a comment: “There even was a youth editorial office in Belarus that refused to publish.”

And everything changed. Salamakha came running to the editorial office, shaking hands with everyone: “Well done! This is the Komsomol of the new era!” So I shifted from being a culprit to a hero.

And what lingered in the soul — a sense of change, or continued confusion?

We refused to reprint Andreyeva’s work, but we did not create an alternative. We were not yet ready for genuine pluralism. We were just lucky; we got away, but they started looking at us more closely. We had to make do with the limited opportunities for freedom available to us.

Writing about Popular Fronts was forbidden when they appeared in the Baltic republics. I took a story about the Estonian movement and published it in the “Abroad” section. They missed it. Then I did the same with Latvia. Again, unnoticed, I rubbed my hands with joy. But when these tricks were finally registered, I was called in and scolded for a long time.

But there was no stopping it. I became a delegate to the Belarusian Popular Front’s founding congress in Vilnius and created its cell in Znamya Yunosti. We held a general meeting at the Press House. The Popular Front was youthful, free, and brimming with optimism in those days. It was not the opposition, but the renaissance movement.

Then I met Viachorka, Ivashkevich, and Ales Susha. The guys asked me to write an article for Naviny BNF about corruption among party leaders at the Atolina urban farm. I did. It was published, and so I became part of the new journalism.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich reports from Independence Square in Minsk. Photo: svaboda.org

Did the new personnel policy affect your decision to leave? At that time, a new editor was appointed to Znyamia Yunosti.

Right, Mikhail Katsiushenka. The circulation dropped, and the newspaper took on a more governmental tone. The boss, as it turned out, was a Kebich man — and generally not the type to push for change. I started working at Narodnaya Gazeta, which Iosif Siaredzich founded in the Parliament. For a year and a half, I worked alongside Mikalai Halko as a parliamentary correspondent. We covered all the events, and political life exploded daily.

By today’s standards, it seems unbelievable: Did freedom of speech really prevail in Parliament?

The mornings would begin with a one-hour session of remarks: deputies were free to speak their minds and express their positions. Lukashenka took full advantage of that opportunity. He spoke loudly, with jokes and slogans. Half of it is emptiness and populism, but he was listened to. And so he gained popularity.

And then came 1995 — the beating of deputies. I was in the hall where the opposition began a hunger strike in protest of the language referendum. In the evening, we gathered and talked for a while. I got home late, and the next morning, I found out that the deputies had been beaten up! They were taken out on buses, tortured. When I met deputy Hermianchuk, he showed me his bruised back. Ales Shut was also battered. I wrote down all the details of the incident in the report, including how the doors opened, how the violence began, who the beaters were, and who was hurt. I handed it over to the editor. I did not doubt that the material would be released the next day. However, the newspaper only published the first part, which was unimportant: description of the beginning of that day, and nothing about its dramatic finale.

And why was the article abridged? Was there a whiff of censorship in the air? The sun went down?

Mikalai Halko was already the acting editor. My article, “Lukashenka has set his sights on the Kremlin,” was one of the reasons Siaredzich was removed. The page with this text was censored.

In it, I articulated a sentiment that no one else has ever expressed verbally. I could sense the “young president’s” intentions from afar when he accompanied Yeltsin during his visit to Minsk Tractor Plant. With warmth in his voice and an insinuating bow, “our president” would then say to the “dear guest”: “Look! This is your factory!”

What about Halko? Weren’t you two working side by side? Did he explain his position or justify himself?

He just said the traditional thing for the state media. “You understand everything, after all!” And I did. We remained on good terms. It was clear he was caught between a rock and a hard place when he agreed to serve as acting editor, knowing he would soon be replaced. That’s what happened. Six months later, another one was appointed. Mikalai left.

The following day, after they cut my publication, I submitted my resignation letter. As a parliamentary correspondent, I realized that if I could not cover the main events of Parliament, my work would lose its meaning. Halko approved it immediately, without arguing.

Svaboda is another world: you take on full responsibility. You are accountable for what you wrote. No one will cover for you; there is no higher authority

I quickly offered the same censored article about Lukashenka’s Kremlin ambitions to the deputy and editor of Svaboda, Ihar Hermianchuk, and he published it promptly. That’s how my work in this editorial office began. Vital Tsyhankou, Viktar Uladashchuk, and Ales Dashchynski were already employed there. Together, we created a newspaper that was later called Naviny, then Nasha Svaboda. The names changed, but the essence remained.

In what ways did Svaboda differ from Narodnaya Gazeta?

It was a whole other world. You take on full responsibility. You are accountable for what you wrote. No one will cover for you; there is no higher authority. You were responsible to both the reader and the editor if you made a mistake. Ihar was a jewel of a man. I didn’t want to disappoint him. It was harder, but much more interesting — a real school of autonomy.

Do you remember the moment when it turned into a real ordeal — when your words determined actual freedom, not just editorial office freedom?

I suppose it began when Pavel Zhuk brought a secret document to the editorial office. The document’s subject was the opposition’s alleged plans to “seize power” and the measures to be taken in response. Namely, harsh operations, even physical destruction, were permitted against these people. The article was published under my name.

A few days after the publication, as I was about to go to work, I noticed a police van parked next to my house. I called Zhanna Litsvina. At the time, she was the head of Radio Liberty and the chairperson of the BAJ. As soon as I stepped outside, a man wearing a raincoat jumped up. A typical KGB agent. He showed me his ID, grabbed my hand, and pushed me into the van. Inside sat a “witness.” It was a young, around 30, guy who wore a strange outfit: a fringed leather jacket and big, heeled shoes that almost looked like spurs — like some Indian. Then I realized that they were being sent out into the streets to monitor, establish contacts, and report back.

Recording with Aleh Hruzdzilovich before his arrest in 2021. Photo: from the archive of Aliaxander Lukashuk

A snitch for all occasions?

They recruited from all walks of life. In the KGB’s main building, they badgered me for several hours straight. They wanted to know who brought the document, where they got it, how they got it, what it was, and why… But at that moment, I had good legal advice and stuck to it: I would speak only in the presence of a public representative. The KGB officers were confused by this, but they did not give up. They resorted to threats, blackmail, and psychological pressure. Ultimately, someone called my investigator. He returned the papers to the folder and said:

“Well, at least sign to confirm that you have been here.” “I won’t. I won’t even do that.” A few months later, Karpenka died suddenly. Then Zakharanka, Hanchar, and Krasouski[4] disappeared. We all realized it wasn’t a game anymore.

Many times afterwards, I thought: They could have done the same to me. However, in 1998, there was still some lingering influence from perestroika, and a modest degree of freedom. That may be why they didn’t take the risk. A year later, their methods changed: they became quiet and secretive, conducting their work without trials or investigations.

And most importantly, that document was authentic. It predicted everything that happened. This suggests that there were still individuals within those agencies with a strong moral compass — those who wanted to prevent crime.

It was a mirror of time in which faith, despair, blood, and the indelible truth were reflected

I began working at Radio Liberty in 2000. I still work there today, except for the time I spent in prison.

During this time, you saw many of the era’s political figures: Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and even Clinton. You were having a meeting with him, right?

But for the most part, though, I watched Lukashenka ever since his time as a deputy. Back when he was still pretending to be a democrat. Once, while taking his comment on the land act, I heard: “The peasants need to be given the land — it will change everything for the common good.” I hadn’t yet turned off the recorder when Lukashenka started giving his comment to the correspondent of the communist newspaper Tovarishch: “You can’t give the land away — they’ll ruin everything, start selling it off, and oligarchs will emerge.” That’s when I realized that this person would say whatever was convenient for him.

Or take the first steps of his presidency. The meeting with a group of journalists after the “blank pages” story was significant. Then, Siarhei Antonchyk’s alternative anti-corruption report was censored from newspapers. He arrived with a menacing guard, and Lukashenka himself appeared gloomy and strict. But he smiled and shook hands.

My senior colleagues encouraged me to speak up. I said, “What you are destroying is a mirror that allows you to see what is really going on in the country. A free press is not an enemy; it’s a tool. Without it, you’ll lose your bearings.”

He listened in silence. Then he tossed in some stock phrases about discipline and state interests. He was flat-eyed. It dawned on me that he won’t hear. He didn’t come to listen; he came to act on his role.

Basically, the monologue before Lukashenka was a bold attempt to defend freedom of speech. If you think about it, you have spent all these years at Radio Liberty engaged in human rights journalism.

I remember the first process that opened this path for me. It was 1996. They tried Slavamir Adamovic in court, who was the first political prisoner of the new Belarus. He wrote the poem “To Kill the President” and got a real prison sentence.

Then came the dispersal of the Chornobyl March, followed by arrests and convictions. Political activists and leaders were forcefully disappeared. I talked to their families. Zavadski’s mother and Zakharanka’s daughter. Those were conversations that are impossible to forget. Grief, helplessness, and yet hope. Pain that does not go away.

Which of the many reports is the most memorable?

Probably when I was detained, but they didn’t notice my camera. It was 2011, the so-called silent protest. People took to the streets and just clapped. No slogans. A silent protest against crisis and fear.

I was near the National Library. There were only a dozen or two people. The riot police showed up and started grabbing everyone. I ended up in a police wagon, too. But they didn’t notice my camera.

We’re sitting in the van, and I could see the road and the policemen’s faces through an opening in the door. I took out my camera and started interviewing other arrestees. To keep the flash drive from being seized, I put it in my sock.

They took me to the police station, where they identified me. Then, something unexpected happened: they let me go. As it turns out, Aliaksandr Lastouski, the police spokesperson, interfered. He was influential back then and actually protected many people. What a period of contrasts! I immediately ran to the editorial office, and an hour later, the report from the paddy wagon was already posted on the website.

The next day, the video was shown on Russia’s RTR: “In Belarus, a Radio Liberty journalist filmed video from inside a police van.” A rare stroke of professional luck.

Some reports bring good luck. But are there any that leave you unable to sleep?

December 19, 2010. Post-election protest dispersal. In the midst of the chaos, I captured footage of Aliaksandr Klaskouski Jr, the son of my journalist friend. He was wearing a uniform, and blood was on his face. I didn’t know it was Aliaksandr at the time. At first, I thought it was a policeman who had switched sides. He later mentioned that he used to work at the traffic police. I called him late at night after the violent dispersal. He could only say, “They’re already at my door.” Aliaksandr recently passed away, and that image is still in my head — like a mirror of time in which faith, despair, blood, and the indelible truth were reflected.

A typical Belarusian prison sentence is spent thinking about how to live from morning to night and from night to morning

Regarding your imprisonment, was there a situation that revealed the inner workings of the system? Not as a journalist observing from the outside, but as someone who became part of it?

Absolutely. I experienced three stages of such discovery.

The first one was autumn 2020. I was detained for the first time and spent 15 days at the Baranavichy Detention Center. It is a local administrative prison, prepared in advance for mass dispersals. Before that time, the former barracks were not actually used. Some said the tsarist troops were stationed there, while others said they were a stable built under Polish rule. It was quickly converted into an isolation facility. There were no substantial repairs. We saw tarps, dilapidated walls, and mold. Some of the cells had already been newly plastered, though. As a journalist, I was thrown into one of the decent cells. Then, I was moved to another one with inscriptions on the walls dating back to the eighties.

I caught COVID there and barely survived. I could hardly stand when I was being released. Prison is characterized by mundane suffering, humiliation, and artificial cruelty.

There were nine of us in the cell. We heard how the newcomers were brought in: dogs barking, shouting, and swearing; people running down the corridor; and beatings and forced floor-gazing. But at the same time, we thought, “We will get out and see how momentum for freedom is building…”

Prison picture of a journalist Aleh Hruzdzilovich

In reality, the protest was drowned out by the repression. Were they targeting specific people? The ones who kept the fire burning?

The second stage began in July 2021. Mass arrests of journalists started. A case has been opened against Radio Liberty employees. They arrested me, Dashchynski, and Ina Studzinskaya. The day before, the teams from Nasha Niva, Viasna, and TUT.by had already been detained.

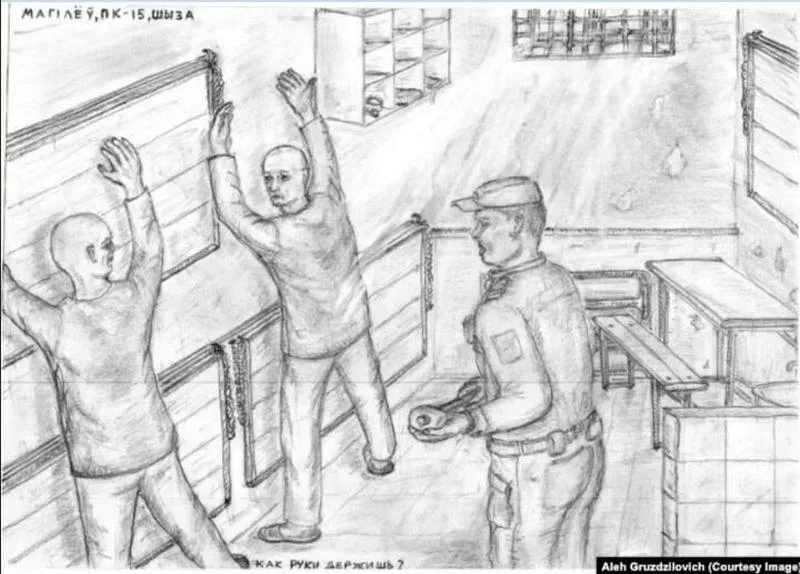

The reality was stark and unforgiving. Dashchynski and I shared a cell at the Minsk Remand Center. I saw our relatives through the window who came with care packages for us, but we didn’t receive anything. The guards didn’t give us anything: no sheets, no food. I later added a drawing of that scene to my book.

There was one criminal in the cell, detained for drug possession. He taught us how to behave in the correctional facility. He explained what to say to avoid being mistaken for “gay,” how to handle things, and what could be picked up off the floor and what couldn’t — a survival education program.

Attitude toward politics changed radically. In 2020, one thought of it as “evil that is mechanically and unintentionally reproduced,” but by 2021, one perceived evil as a system.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich on the first day after the unexpected liberation. Vilnius, 2022. Photo: svaboda.org

The third arrest, six months later, probably revealed the system with no masks or coincidences.

When I arrived at the quarantine unit, I heard: “Are you a political? Expect the punishment cell right away.”

And I indeed ended up there. They came up with the reason. Allegedly, there was an inconsistency in the list of my personal belongings. Like, something was missing. Under the guise of a legitimate punishment, I was sent to a punishment cell.

The whole process looks pretty technical. First, they write the report. Then, there’s the commission meeting, which supposedly decides your fate. However, everything has already been agreed in advance.

I was brought to the prison warden’s office, where several other officers were present. He looked at the reports, saw “Radio Liberty,” and became angry. “Did you come here to spread liberty?” he asked.

He shouted, interrupted, and threatened. When I tried to answer in Belarusian, he almost completely lost it and ordered, “Deal with him. Put him in the SHU or send him to the ‘untouchables’ unit.”

As you walk down the hall, you can’t tell whether it’s just a threat or the verdict has already been passed. You know that words can carry real danger. And then they take you to the punishment cell. They beat you there — from behind, without a word. Then they leave you alone in solitary, and that’s it. The first evening is like sinking into the abyss for the first time. The night is the hardest: sleep eludes you, time stands still, and you feel as if you no longer exist. In the morning, you only think about making it to the evening. And in the evening, you think about making it to morning.

That’s what life in a Belarusian prison is like.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich in the Seimas of Lithuania, where he was awarded the “Hope for Freedom” award. December 1, 2022. Photo: BAJ

After all of this — Svaboda and prison — is there a sense of generational defeat? Or your personal?

I don’t feel defeated.

But I can smell resentment. I feel it from many. From people I grew up with, worked with, and who stayed on the sidelines. I didn’t see them at the rallies, in the crowds. Some of my classmates, colleagues, and relatives simply soothed their consciences with the mantra, “Everything is calm. Everything is fine.” Even now, they still don’t want to change their worldview. Official credentials, positions, and constant fear protect them.

However, others “overran their banks.” I saw them in a human chain that stretched from Kastrychnitskaya Square to the Red Church. Yesterday, they voted for Lukashenka, but today they said: “We are disappointed. If nothing changes now, we are quitting.”

This is Belarus. It’s not black-and-white; it’s lively, complex, and diverse. Most importantly, it is capable of awakening.

But why did some catch the wind of the age, while others didn’t think of any sails and didn’t set off anywhere, content with “being well-fed”?

There is no universal answer. After all, everyone has a different experience and responsibility level. In the broadest sense, the Soviet school system taught people to keep their heads down, avoid risks, and not ask questions. It was injected into our blood. And it’s not easy to get rid of it.

I recall one colleague in particular, whom I won’t identify, although his name is quite familiar to many. He worked for a state newspaper his whole life. He’s a good journalist, and once boasted to me that he’d never been abroad. Not even to Poland. It’s a vicious circle: a person has never seen how things could be different and doesn’t seek to do so.

What opened your window to another world?

This is not just one or two events… Here is one example. On my father’s table once lay the poem A New Land by Yakub Kolas, written while he was in prison. It wasn’t part of the school reading list, but it helped me. But someone did not have that opportunity. Instead of hunting for cool books, they learned how to catch gudgeons.

There were enough top-class job jockeys in the orbit of Lukashenka’s power vertical. But there were also people like Piotr Vasiuchenka, who was a model of national consciousness: a remarkable creator and scientist, a genuine Belarusian.

He raised and struck a spark out of so many people! And not only in science.

Thanks to people like Piotr and others whom I did not have time to mention, a new generation has emerged imperceptibly. To be honest, I didn’t expect 2020 to be so massive. Before 2020, when I watched columns of activists numbering just a few hundred in a two-million-strong Minsk, I thought that, at best, the 2010 election scenario would repeat itself. But I witnessed a powerful revolution!

Aleh Hruzdzilovich at the conference “Belarusian Journalism: Where Tomorrow Begins”. Vilnius, September 16, 2025. Photo: BAJ

So what supports my faith?

It is Radio Liberty, to which I dedicated half of my creative and civic life. A prison guard thought it was American, just as propagandists often claimed. I’ve seen it countless times: for everyday Belarusians, radio served as a mirror, offering a genuine reflection of themselves and their country. Together, we are fighting for the Belarusian language, dignity, and the right to call a spade a spade.

I recall one incident at Minsk Remand Center. An older man who was detained for his comments recognized my name and remembered my articles from the Znamya Yunosti times. It’s impossible to ignore the fact that my work and the lives of my subjects were not in vain.

If people in prison remember our truth, then we lived with dignity.

The project “Voice of the Freedom Generation” is co-financed by the Polish Cooperation for Development Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The publication reflects exclusively the author’s views and cannot be equated with the official position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.

[1] Vladimir Vysotsky was a Soviet singer-songwriter, poet, and actor who had an immense and enduring effect on Soviet culture. He became widely known for his unique singing style and for his lyrics, which featured social and political commentary in often-humorous street jargon.

[2] Vasil Bykau was a prominent Belarusian dissident and author of novels and novellas about World War II.

[3] The Black Hundreds were reactionary, monarchist, and ultra-nationalist groups in Russia in the early 20th century. They were staunch supporters of the House of Romanov, and opposed any retreat from the autocracy of the reigning monarch. Their name arose from the medieval concept of “black”, or common (non-noble) people, organized into militias.

[4] Opposition leader Henadz Karpenka’s death and the disappearances of former Interior Minister Yury Zakharanka, opposition leader Viktar Hanchar, businessman Anatol Krasouski, and later journalist Dzmitry Zavadski were blamed on Lukashenka and his security bosses. These crimed have not been investigated until now.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia