Two-thirds of journalists in exile change their profession

Work in exile does not mean a happy end – it makes inequalities deeper. Furthermore, two-thirds of journalists in exile leave the profession, while working in editorial offices tend to be more sustainable. Researcher and Professor at Salzburg University, Hanan Badr, discusses the collective experience of journalists in exile.

Hanan Badr. Photo: Universität Salzburg

Different countries had overlapping experience

Studying journalism in Cairo but working in an academic environment in the EU – this is a brief description of Hanan Badr’s career. She is a professor at Salzburg University in Austria and heads the division of Public Spheres and Inequality.

Her interest in journalism research emerged during the unsuccessful Arab uprisings in 2010–2011, “when in the Arab region – in Tunisia, Libya, Syria – there was a push for democratization and we know that they failed. This is part of my personal history, when I became interested in research,” says Hanan Badr.

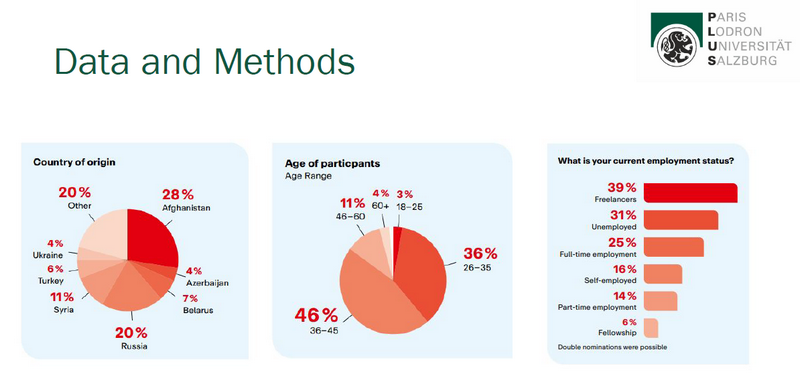

Through interviews with media workers, she studies journalism in exile and notes that its scope has become unprecedented worldwide. Based on 90 English-language questionnaires and 50 interviews, the professor published on 2024 study titled “Exiled Journalist Communities in Germany,” one of a few works on the topic.

Respondents were from three regions: Eastern Europe, Western and Central Asia, and the Arab region, with Belarusians making up only 7%. Why? “The majority of [the Belarusian] community does not live in Germany – but there are many overlapping between different communities in exile,” says Hanan Badr about their collective experience.

An authoritarian backsliding

The phenomenon of journalism in exile is not new, Hanan Badr explains, and it existed even during the time of the Roman Empire. Its scale increased over 10–15 years, but the structure of aid for journalists in exile is developing more slowly. According to reports from the Committee to Protect Journalists and other organizations, aid to journalists in exile increased by 227% between 2020 and 2023, Hanan Badr notes.

“I conducted interviews with media representatives, policymakers, journalists. One of them said that the applications from journalists increased fivefold over the past three years. Of course, funding did not increase fivefold,” she says.

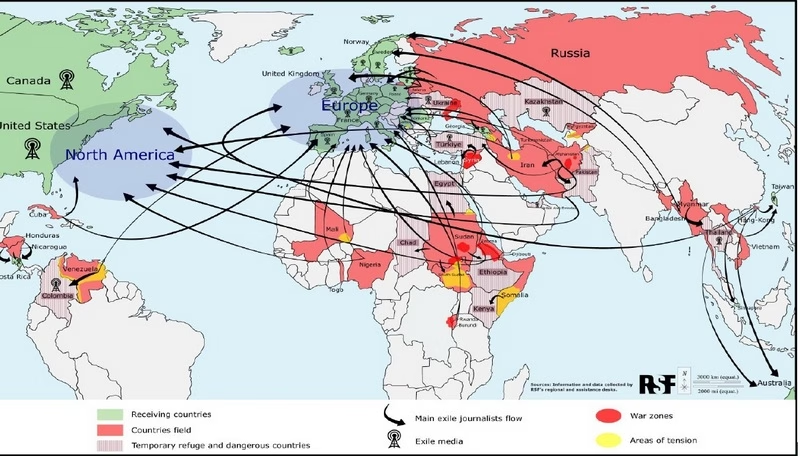

Working conditions for journalists have also worsened in recent years – this can be seen on the press freedom map made by the international organization “Reporters Without Borders”. “The Press Freedom Map in 2025 by ‘Reporters Without Borders’ visually shows the authoritarian backsliding in countries like Russia, Belarus, Turkey, but also my country of origin Egypt which is in red. And even countries […] like the United States,” says Hanan Badr.

Press Freedom Map, 2025, “Reporters Without Borders”

The geography of journalists in exile is visible on another map from the same organization. However, the researcher adds: it is incomplete: “There are very many undocumented cases”. For instance, not all journalists speak English or French. Cases in Paris, where the organization is located, are well documented on the map, while movement to neighbouring countries – often the first destination – is poorly reflected.

A map by “Reporters Without Borders” shows the movement of journalists from countries where they face pressure to Northern and Western Europe and North America. However, it does not show that there are very many neighboring countries that became temporary refuge.

A famous journalist who no one knew

Some journalists stay home and leave the profession, expecting to avoid persecution. Others are limited by responsibilities to care for children or other relatives in the country of origin. By the way, the researcher notes, part of them are proud to be media professionals, while others are equally proud by calling themselves activists.

“And some people, again, switch from one group to another. This is a thin line, such a vaguely defined one,” says Hanan Badr.

The paradox of exile is on being chosen for security reasons – but it doesn’t mean a happy end. It leads to instability on other levels. The main issue is not renting a flat or find a school for children, but existence itself – the professor quotes one of her interviewees. She stresses: most journalists in exile did not want to leave.

At the same time, some of them find good conditions in a new place. “One of the respondents was a very famous Turkish journalist and editor. He really received multiple offers and openly shared with me whether he should go to Germany or France…,” says Hanan Badr.

But this is rather an exception. Journalists in exile often find themselves on the periphery of their profession, even if they were celebrities at home, which causes stress and mental health issues. “I was once at a conference, and a person entered, he was a very famous Afghan journalist, and Afghan colleagues went to greet him. But I didn’t know him; in Germany, where the conference was held, no one knew him at all,” says the researcher.

Language barriers and relocation lead to the loss of usual resources and audiences. Or, instead of an audience in one country, journalists begin working for several, transnationally. The question of financial viability emerges, and relocation makes deeper inequalities related to gender, method of legalization, and others. “Many people do not know what to do,” says the researcher.

Journalists in between temporary and permanent emigration

Time is a leitmotif of work in exile: it is needed for emotional recovery and to heal the consequences of tortures or detention. Over time, people also face dilemmas and negotiations with themselves.

“They hesitate between different mindsets: from ‘I did not want to detach myself from the resources and friends I had’ to ‘We are here to stay forever’,” says the professor.

A person may deny reality: while being located in exile, in his mind he is still at home, with his books and his love. A new personal and professional identity is built through confronting such dilemmas and healing after such a rupture. However, the less a person achieves on status and prestige – the easier it is to leave it in the past, says the researcher, and she links this to age.

Over time, according to the research, 60–70% of journalists in exile quit their profession, because projects end or they are unable to find work in the new geopolitical conditions. These conclusions are based on a survey of a group of journalists, the majority of whom are middle-aged ones (26–45 years old), in the middle of their careers. At the time of the survey, only 25% had full employment.

Happy stories and support

What should be done? Perhaps the answer lies in the researcher’s conclusion: she notes a higher rate of professional survival in the media organizations compared to journalists working independently. Although, of course, the media organizations in exile face problems with funding as well.

“Individual journalists, working on their own, are less likely to remain in the profession,” says Hanan Badr.

But it does not mean their life is bad, the professor explains – it just means their professional interests shift from journalism to other fields, from activism to academic careers or political consulting. “I did not have the time to highlight also some happier stories, like the couple who just opened a restaurant and they stopped being journalists and found a new happy existence where they came to peace with that,” says the researcher.

“We also have the Syrian case, where after 14 years of civil war and armed conflict and losing homes, Syrian journalists have at least had the hope that maybe they will return back home. Even with all the trauma and the emotional difficulties of returning to a war zone”.

The text is created with the support of the Council of Europe Project “Strengthening the capacities and skills of Belarusian journalists and media actors in exile”.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia