A Fair King

The first release of this interview by Tattsiana Melnichuk with Aliaksei Karol was published on our website in May 2015. We already knew about Mr Karol’s cancer at that time, but nobody expected that he would leave this world so soon...

I was very persistent in trying to obtain this interview because everyone whom I probed about the “hidden birthmarks” of editor Karol1 first and foremost stated: “The King is fair!”

Melnichuk: It is known that journalists are talkative and quick witted, and when it comes to gossiping about chief editor bosses they would rarely hold back. But journalists of your newspaper are easily and naturally giving you unforced compliments, without quotation marks. I don’t want to provoke you into a self compliment, but what are you doing to them to earn such a favourable feedback?

Karol: I doubt I can answer this with any clarity because I never thought about this… Some time ago, in the early 1990’s, we had a goal – to form a newspaper. Everything else was done and worked out on the job, with the flow. It was a normal thing: a concept is born, discussed, adopted, and into this concept authors write materials.

If the concept proves bad, one needs to change it, discuss it again. If this is done openly and collectively, there is no ground for arguments and offense.

The second principle that I am consciously adhering to I would define this way: a person does those things best, and writes on those subjects best, to which he or she is naturally attracted. So the author chooses, and I choose what the author does best, and so the principle of our partnership is formed.

In addition – and everyone in our team understands this – the pay depends on the input into the common work. And when the chief editor and other editors are no richer than staff writers that is also valued and positively impacts the climate in the team. Unfortunately, in our independent papers one cannot count on high profits, but it is a duty of the editor to provide for at least a “non-hungry” level of pay to authors and also to provide transparency on the newspaper’s budget.

Aliaksei, overall, are you controlling your writers?

Karol: I don’t particularly need to: we agree who does what, and it gets done. Some things of course I monitor, some things we discuss, some things I argue with, but that is normal.

I wouldn’t call myself a particularly democratic manager, but I am also not an authoritarian one, to such an extent as to force a change in position or opinion of the writer. We have a normal atmosphere in the paper, and I am surrounded by clever people.

Thank you for relating to me the feeedback on myself from our “smoking room”- in our team we are not used to waterfalls of compliments. Jokes, mutual teasing are our normal behaviour. Even when we congratulate one another, we do so without much pathetic, more like with friendly teases.

How to Reach Concord in New Times

You mentioned creating a newspaper in the early 1990’s. Did you mean Zgoda2?

Karol: Yes. The formation of the Novy Chas3 was a forced act, because Zgoda was shut down by a court decision in 2006, on the eve of the presidential elections. At that time, one of the candidates to the post of the president was Alexander Kazulin. In his speech to the All Belarusian Congress, Lukashenka threatened that “the little paper” that supports Kazulin would be shut down and its journalists, if they would be found guilty, would be put in prison.

The shutdown of Zgoda was perhaps the first instance of closing down of a newspaper by a court order in history of Belarusian journalism, but at least, thank God, the journalists were not imprisoned. One year later (also likely a unique instance) we managed to create another newspaper. That was very difficult.

With the help of BAJ we carefully studied laws and regulations and found some disconnects and gaps. We also carefully avoided mentioning my name in that attempt. It first appeared only in the second issue of the Novy Chas.

For the Novy Chas, I owe the debt of gratitude to the Belarusian Language Society, Aliona Anisim and Aleh Trusau. They are the ones who started the newspaper and passed on to us the naming rights and registration. Until we started our cooperation, the Novy Chas published 48 issues, but it was coming out irregularly. By now, the Novy Chas has run close to 450 issues.

So the Novy Chas is a glaring example of what can be accomplished through cooperation of pro-democratic groups, organizations and individuals. We will always remember the Belarusian Language Society’s deed, honour and respect be on them.

At the end of 2007, already the Novy Chas, we were again under threat of shutdown. But we managed to defend the paper, in large part thanks to the solidarity and support of all independent media in Belarus that started a massive campaign in our defence. International reaction, especially that of the high level EU leadership, also helped.

To the Novy Chas you brought with you the Zgoda team?

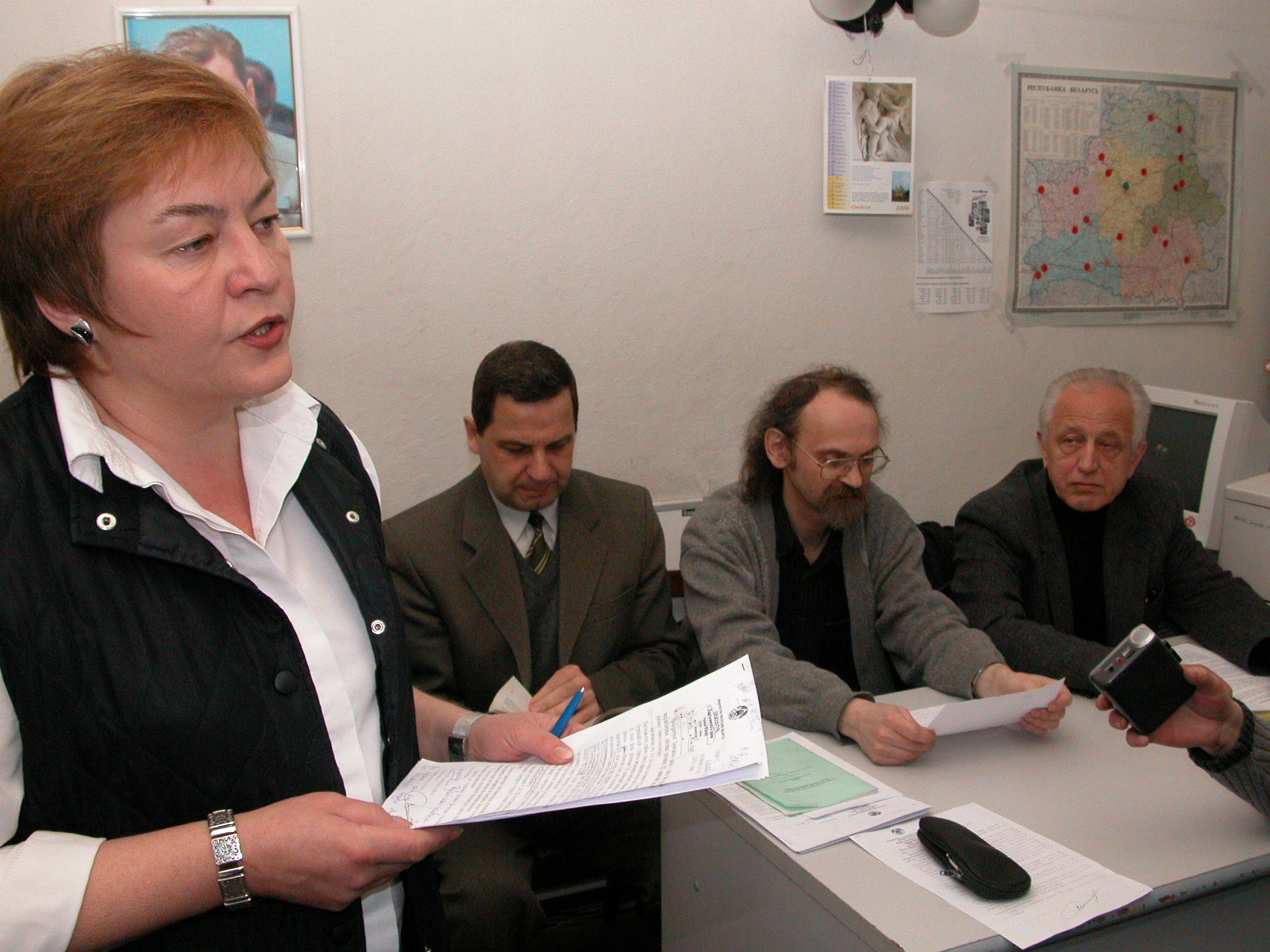

Karol: The core of the team was preserved. That is first of all Aksana Kolb, deputy chief editor, and Sviatlana Piarouskaya, style editor. Both clever and beautiful ladies, organizers, journalists. The ability to do everything is another challenge in fighting for democracy in the severe conditions of authoritarian half-underground. The moment we understood that we might have a chance to renew under a new name, everyone gathered together, and Aleh Novikau (also known under his pen name Lyolik Ushkin) even returned from Ukraine. Then new people came too, and they merged into the team and they recognized the Novy Chas as part of their identity. This is a team, not a bunch or mercenaries, or daily labourers. Maybe that’s why we manage to work on the principles of fairness and solidarity.

The Novy Chas (the New Times) – is it just a name or truly new times for a group of like minded colleagues that came over with you? When I am recalling Zgoda, as it was then, the first thing that comes to mind is that it was a party newspaper.

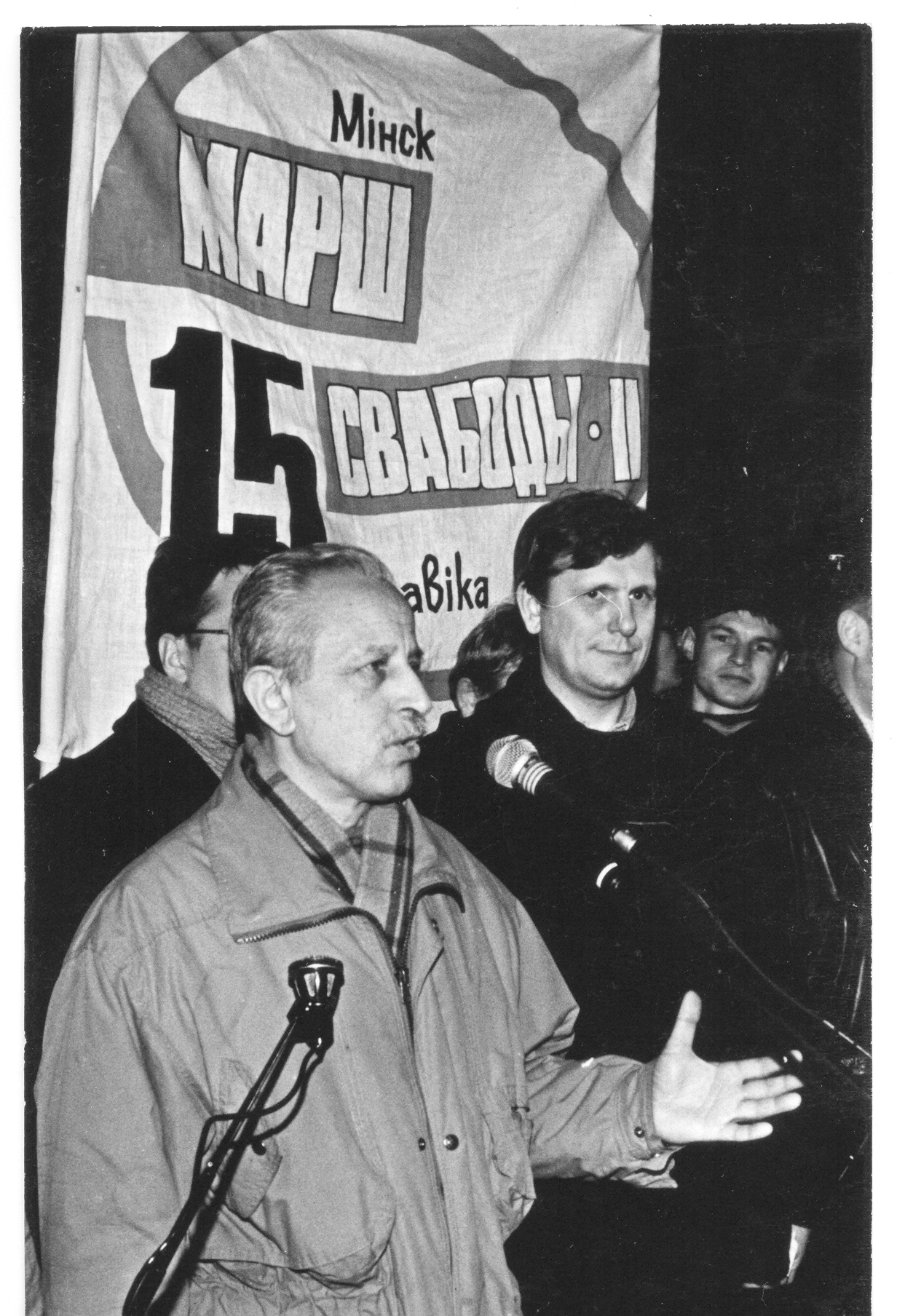

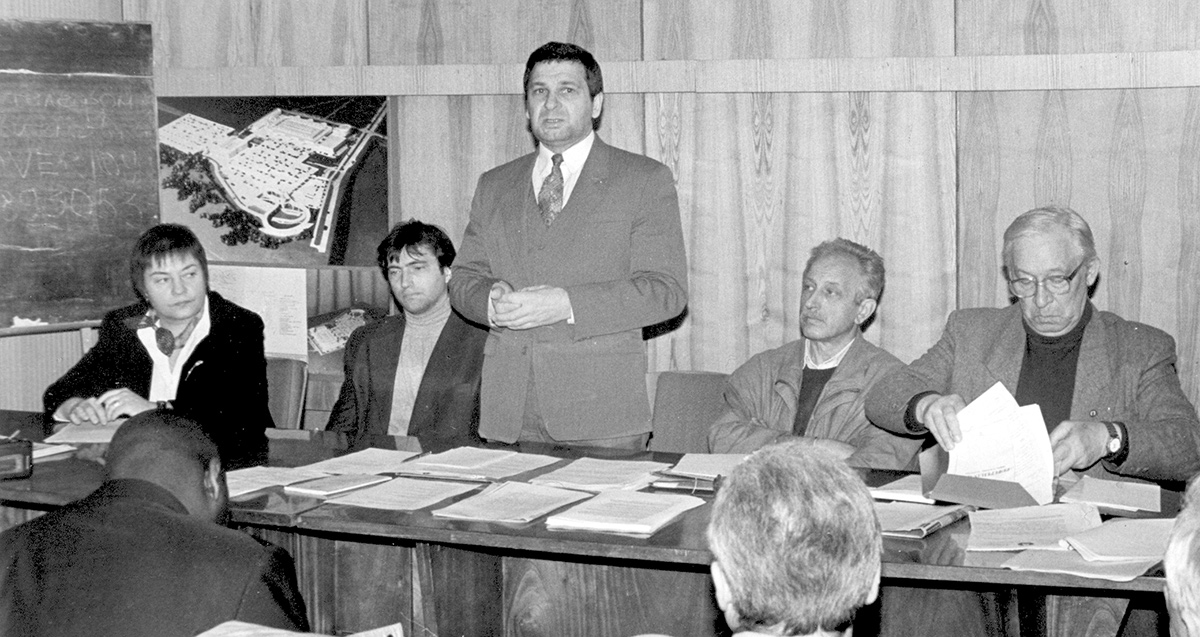

Yes, Zgoda was created as party newspaper, by the Party of People’s Concord, which subsequently became the Belarusian Social Democratic Party (Hramada). Zgoda was formed on the basis of the magazine Political Interlocutor (formerly, an official magazine of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic). The magazine by then lost all viability and could not compete – that was the time of the freedom of press and democracy, the early 1990s! Henadz Karpenka, the head of the Party of People’s Concord, was offered to buy out the magazine, pay its debts, and then take over everything. I later regretted that we did not do this, did not preserve the magazine, even under the old name, but changing its content.

But we made a newspaper instead, having decided that we needed a more operationally mobile medium than a magazine. By the way at that time Zgoda counted 47,000 subscribers – a consequence of the elevated reader engagement amid the thirst for information of those times.

As for the partisanship, in Zgoda, even in those days, in my opinion there was not a lot of it. But the myth of Zgoda as a party paper, the cliché, got stuck. It took us many years to wash them off. We even ordered an independent expert review, and it confirmed that we devoted less space to the social democratic party and its leaders than newspapers unaffiliated with political parties.

And Zgoda was a truly “party media organ” in the proper sense for maybe three months maximum. I realized soon enough that the party paper route was a dead end, the world was free of partisan media, and we had to rid ourselves of the party affiliation. We discussed this with the party fellows, with Chairman Karpenka and decided: let us not repeat the Soviet era mistakes with its party censorship of press. A party can have leaflets, newsletters, and so on, but a mass newspaper cannot be a party organ. And so we became independent.

But I remembered that whole story very well, and therefore when we created the Novy Chas we decided clearly: no party affiliations, no dependency on any party.

The choice of language played an important part in our concept of the Novy Chas. In Zgoda we ran coverage in both Russian and Belarusian. And it always so happened that the Russian language exceeded its quotas: sometimes a writer found it easier to write in Russian, or we did not have the time to translate, or something else – and, ok, fine, let it go!

Aleh Trusau, the founder the Novy Chas who was passing it to us, had a principled position: you want the title, only in Belarusian! And I agreed: the Belarusian language for Belarus is indeed a matter of principle!

And the language in essence already begins to drive the concept. The Belarusian idea, formed back in the beginning of the 19th century, was based on the value of the language, the culture, as foundational for building the statehood and independence.

And those became the main pillars of our concept. Plus we added three full pages to foreign coverage – not just reprint from other sources, but wholly original content, an attempt to create context for making sense of our own, Belarusian, situation against the backdrop of global developments.

Our another important principle – to write about serious things, but without the artificial intellectualism.

Aliaksey, as the chief editor, do you prefer to work with younger journalists, or more mature ones? Or perhaps the “aces” that came with you from Zgoda are like “sacred cows” in the Novy Chas, while the young ones are working their butts off to make a name for themselves?

We have never had the problem of “aces” and the young ones. Like all independent newspapers, we do not have the resources to keep a large team. The paper is made by nine full time persons; over twenty more write for us free lance. And even the so called “aces” are only around forty now. We do not differentiate by age or past achievements: if a 20 year old writer produced a worthy article, both myself and the editorial team will pay him proper dues just as they would to an older veteran.

A year ago Vika Chapleva, a second year university student, came to us with a good story. Now two more student journalists came, and their materials run in both print and online.

I am remembering your own team, Belaruskaya Maladzezhnaya. Siarhei Pulsha, who worked there, now works with us. Before he came to us he worked at BelAPAN, was producing short informational pieces. When he came to us and we were discussing topics for him I said: “Write the way you feel.” And he opened up, he is wonderful in analytics – political analysis, portraits, recognizable by his subtle irony, own style, without exaggerations, factually correct.

The task of a media leader is to help the writer to find and demonstrate his talents.

And those who started the paper, they used to be young, and now they are mature… Our team’s average age is around 40. But this average number is so high only thanks to me, my 70 years.

On the Harm of the Revolutionary Romanticism

Aliaksey, where does your last name, Karol (Belarusian: King) come from? Do you really have royal roots? Or is it from the Western Belarusian word karol that means a soft furred domestic rabbit?

In Belarus, by the way, there are many people with the family name Karol. I got curious about it – there are plenty of Karols in Uzda and Byarezina districts. My father came from Byarezina. The researchers I talked with about this believe that in Belarus that name comes not from royal palaces but from excellence at work: a king of his craft, so to speak. And so here and there talented craftsmen became “kings.”

You come from the country side?

More like from small town, a district centre. On my mother’s side, great grandmother was an indentured peasant. So I am not from nobility (and am underlying it to those who are now actively looking for blue blood in their veins), I am a peasant, I don’t have the noble pride. But my grandfather was a forester, it was a fairly high local position at that time.

My father was an orphan. When his father kicked him out of the house at the age of twelve, he was homeless for a while, and when he was caught, he became an apprentice at a smith shop, then a factory worker, and finally went to vocational school. The World War II found him as a local youth affairs official in Bialystok, at the very West of Belarus then. He did not even manage to enlist properly – joined a spontaneous military formation and retreated with it, amid constant combats, to Moscow, broke away from encirclement. He fought the entire war, with infantry, at the front, made it to Konigsberg, Eastern Prussia. My father’s penultimate job was the District Executive in Smarhon. As a consequence of the war wounds he had his leg amputated, and after that was transferred to Maladzechna, where he headed the beer factory for a while, then retired.

So Smarhon and Maladzechna are my native towns. Until the seventh grade I studied in Smarhon; finished secondary school in Maladzechna, from there entered the Minsk Pedagogical Institute, history department, having worked a year first – the first attempt to enter college was unsuccessful. Then served in the army, came back, finished the history department, with distinction. Then I was directed to work to the Academy of Science, Institute of History.

I know you have a PhD in history. What was your dissertation topic?

Post war Germany, 1945–47. The Soviet occupational administration in East Germany. Policies of the allies in Germany after 1945.

Wow! A high risk topic even now!

As well as very interesting. I chose it myself, I was fortunate that my advisor in the Institute was Dr Illarion Ihnatsenka. He had a principle, which I took up for my own work with people: free search, work on what appeals to you.

I was assigned to the department of history of socialist countries, headed by Alexander Matsko. He too did not strangle free thought in his department.

I would not say that my PhD thesis was written then as I would write it now. But it is from that topic, I think, where came my critical assessment of everything that was happening in the Soviet Union. Because I had that topic, I gained access to secret archives in Moscow, archives that required special authorization. In the archive, I had to hand copy what I needed from the documents into my own notebooks, which were numbered, collated and stamped by the librarians. The notebooks were sent to the First Department of the USSR Academy of Sciences, there, I had to again hand copy from them. I was allowed to use the findings in my research but not make references to the source. I managed to obtain allowance to mark “Archives of the Soviet Military Administration” as the source. Nothing more specific than that.

In the archives I came across special briefs by TASS (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union – the official news agency of the USSR). They were marked NFP – not for printing. Among them were translations of foreign comparative historical research of the Stalin and Hitler regimes. Those were massive type written volumes, made in one copy only, for the high officials. Forgetting my own research, I was consumed by reading them.

So it actually makes sense that totalitarian regimes limit access to archives – historical documents provoke the mind, awaken doubts, critical thinking, and in the secret closed off archives free thought is born.

The first movement in my mind was understanding of the need to cleanse the socialist idea of Stalinist stains, return to the original – moral – brand of socialist “with human face.” After that came the understanding of the very concept of socialism and bolshevism in their true reality. And the shock of realization that it was from that very concept that the totalitarian regime began.

It so happened that when the freedom of speech started to emerge I was the first to tell about the Belarusization policy of the 1920’s (a policy within the Soviet Union that allowed, and even encouraged, formation of the national culture and institutions in Belarus as part of the USRR). I even wrote two articles, and they were published by the Sovetskaya Belorussiya, still an organ of the Communist Party. The journalists who worked there later told me that when my article arrived, marked “urgent” to boot, everyone was sure that the Central Committee sent another propaganda piece. When they opened it and started to read their hair stood up – under the Central Committee stamp, a totally subversive article arrived!

The perestroika opened the floodgate. At the Central Committee order I prepared voluminous reports, case for rehabilitation of Usevalad Ihnatouski and Zmitser Zhylunovich (Belarusian national activists, government officials and authors executed by the Stalin regime in the 1930’s) and all other repressed Belarusians. Later they did not even have to be rehabilitated, life itself rehabilitated them. I wrote a book about Ihnatouski – the architect of the Belarusization of the 1920s.

Today I would re-write my works from the early times – the study of the 1905 revolution in Belarus, and several articles. Back then I did not have the opportunity to receive unbiased information. I realize it now how hard it is to be an objective researcher when you are submerged under an avalanche of ideological brainstorming, prefabricated information, when not just single bricks – entire walls – are taken out from the historical truth, literature is filtered, and you just cannot break through all that. You feel that something is not right, but you lack the proof, and the tiles refuse to make a mosaic!

The totalitarian regime always counts itself above the moral norms, but makes everyone else subject to a moral standard, and forces down on everybody a brand of revolutionary romanticism. Through that romanticism we perceived Bolshevism and the Soviet rule as something just.

Unfinished Business

Aliaksei, do you have many friends?

Normally not too many friends. The closest, Lyavon Loyka, sadly passed away. He was sixty years old. He was a friend in life and in cause, he and I were implementing the party project together, our first newspaper. I miss him very much.

I have friends in the paper, in the party, but I feel Lyavon’s absence.

And have you been lucky with women?

Yes, I have: from childhood I was surrounded by clever and beautiful girls and women. In my life there is one woman, the mother of my children. When we married, I was just a third year student, and a youth organization leader. The joy of my life, and my best product are my children. They are, by the way, my friends too. We have complete mutual understanding, respect. They chose their destinies themselves, and quite successfully. That is pleasing.

Do you retain personal connections with the “party diaspora?”

I am not a party person any more. It is healthier for a journalist, especially in our situation, under an authoritarian dominance.

I left the Social-Democratic party after the upper hand in it was gained by the group of members who voted in favour of removing Kazulin from the post of the Chairman while he was in prison. Lyaukovich became the Chairman at that time. This kind of decision taken against Kazulin, who was behind bars, I considered amoral. Of course electing a new party leader is a normal thing, but not when that leader is in prison and on top of that is holding a hunger strike.

These internal squabbles only play to the hand of the authoritarian regime. Such regimes always use personal ambitions and weak institutions in order to speed up marginalizing their opponents. This is also normal under repressions. The Belarusian Social-Democrats may have been the first ones to travel that road but today we are seeing something along the same lines in other oppositional institutions – their activities are limited and controversial and the level of authority in the society is quite low.

It seems that in the community of independent media things altogether look a lot more coordinated, there is more solidarity, even though there too various things can happen. How do you, a man with a well known political biography, feel in the shoes of a newspaper man? Do the old party conflicts get in the way of interviewing men of politics? And did the media brotherhood accept you as one of their own?

My relationship with men of politics is normal. One reporter’s principle is not to quarrel with those you are going to interview. That’s one thing.

Second, in my own past political life I managed to not cross the line between a principled debate and a personal hatred. For example, within the Social-Democratic movement I had a fairly complicated relationship with Mikola Statkevich. But, shortly before those elections after which he was thrown behind bars, we had a wonderful meeting and talk. We noted – both he and I – that with all our past arguments we never made public negative statements about one another. And so there were no obstacles for us to meet later and for me to interview him about his activities and his party.

At the Novy Chas we hosted a series of round tables with political figures of various directions. Even those who are in argument with each other we brought together and presented all views in our reports. Unfortunately, neither ourselves nor other journalists were able to influence our opposition’s ability to reach these past presidential elections with a single candidate. The unity has evaded us.

As for the journalist community, yes, I agree that this really is a community with higher solidarity. I see two reasons for this. First, we understood that when there is pressure we can hold up a bridgehead of free speech only by mutually supporting each other. Our own examples – of Zhoda and Novy Chas – support this assertion.

Second, every medium is fairly autonomous. We are not competitors to each other, we do not have to elect a single candidate. We have solidarity in our acts and our words but we do not have to agree on each professional move, as this is necessary in a political party. Every newspaper walks its own way, but in the common direction, based on objectivity, democracy and freedom of speech.

Yes, we must have each other’s back and not allow them to suffocate us. This is possible. A totalitarian ideal is a state of no independent media, no free outlet. So far the authorities have not managed to reach this “ideal” – in the media space, the opposition managed to keep that bridgehead of freedom. This is our common credit.

Do you regret leaving behind the political life?

In my 70 years, looking back at the life I lived, I only regret that we did not manage to establish and realize victoriously the idea of a democratic Belarus. That idea was fairly widely spread out in the society after Belarus gained sovereignty. The debate as to why that idea did not come to fruition continues to this day: why we didn’t manage, or was there a real chance?

I think that there was a real chance but we lost it. We did not understand how to mobilize all the resources that alternative had. By the way, all this time to this day, all these twenty years after the failure, this situation has not been properly analysed. Neither by the political opposition nor by analysts.

And what we did not manage to do, we left to our children – they will have to finish it. And for this, I feel a sense of guilt. My daughter is comforting me though: “Your generation did all it could, with all the faults, you created a foundation for a new, and this time victorious, attempt for a democratic reform.”

What Awards are Given For

I am very impressed by your reported, Zmitser Halko, who wandered around Ukraine and wrote a series of excellent materials. Were you worried about him?

I was worried, and we continue to be worried. That was his choice, his decision – I have no right to send a reporter to a frontline of a war, take that kind of risk. We helped him as much as we could. First it was Maidan. And after that, the hot pathways of war. His reports and feature stories are very talented and sincere. I would compare them with the war reports by Hemingway or Saint-Exupery. It is that level of making sense, that same anti-war intensity – not a theatrical pathos, but lived through, shown through the suffering of the stories’ protagonists.

That is our luck that we have such a reporter. But I would prefer that there were fewer such opportunities to discover talents.

You gave Zmitser a very high mark, and so did the readers. Did he succumb to a star disease? Was the team shaken that one of its members reach so much higher than others?

No, neither star disease nor jealousy were observed. He returned, and went back to Ukraine, today he is at Mariupol. I admit that it is not easy for a chief editor to manage a reporter like that: the paper may have one need, and the reporter — another. You have to adjust. You cannot stop such impulses, he will do it anyway, as he thinks of it, so it is better to find a compromise.

Our team has many various types but all correctly understand Zmitser’s “special schedule.” He chose the subject of Ukraine, others chose other subjects, and in their themes they are not any less talented.

You speak so highly of every member of your team – everyone is talented, and everyone is worthy of respect. In your life, did you experience much praise?

I cannot recall that I have been reprimanded for much. Praise, I suppose yes, I got. At school I got praise for history and literature, but not for maths. Military service I took as a necessity. Officers were persuading me to join a professional military school but I knew firmly that orders and me in uniform – that could not go together.

You finished the army service in the rank of sergeant?

Actually, lieutenant. I served in the Soviet contingent in Eastern Germany , from 1964 till 1967, three years. There was that tradition in that contingent that men with 10 years of schooling during their third year of service received two months of special training and were discharged with a lieutenant rank.

I served in the tank corps, on the then very advanced T‑62 tanks. After Germany was reunited, I watched on TV how those tanks were being transported back to USSR, for scrap metal – such enormous quantity of them was there in the former socialist block.

I do admit, I am guilty of being a “storm trooper” when it comes to deadlines. I finished my PhD thesis at the last moment, and always, at the last moment before the deadline, I finish my articles. I often got blamed for that, but the product seems to have always turned out well enough.

Do you have journalistic awards?

Yes. In 2008 I received the Knight International award, named after an American journalist by that name. This is a personal award. And our newspaper received the Zeit Award in 2009. Such is the uniqueness of the Belarusian independent journalism – we receive international awards for resistance to authoritarianism, to repressions, so to speak, for journalism under harsh conditions. I would wish that the situation changed and we had a competition of talents and received awards for quality journalism in normal conditions.

The most amazing, the brightest thing that happened in my life is this freedom of self realization and an attempt to a political transformation of Belarus. I consider that a great happiness that history threw me that chance to break away from a totalitarian regime. This sweet feeling of stretching your wings, speak and write what you think. Until 1994 it was in general free, and after the totalitarian regime was reinstalled in Belarus, freedom remained in resistance to it, in the independent media, in the Novy Chas. That sweet feeling of free word! I feel it at a physical level.

P.S.

We ended our conversation on this emotional civic note – as befits people who have been tirelessly building their long human and professional way.

But before saying good bye, Aliaksei suddenly smiled:

You know, I was being talked out of becoming a journalist, and in fact did get talked out, and still, I am here!

It turned out that he started writing to a district newspaper when he was still a schoolboy, and after graduating from high school was not sure – history or journalism? And so an experienced writer of the district paper sincerely advised: “Stop this journalism nonsense. Go and get a normal profession, and if it really gets to you, you can always find a job at a newspaper with any education. But if you get a journalism major, you will not get any other job!”

Such is our professional secret.

1. Surname Karol translates from Belarusian as King. Among the Belarusian journalists, Mr Karol’s surname also became his affectionate nickname, for the qualities later described in this interview.

2. Zgoda was a newspaper created by Mr Karol in 1992. Its name translates from Belarusian as Concord

3. Novy Chas is the second newspaper created by Mr Karol and the one he headed at the time of this interview and till his death in September 2015. Novy Chas translates from Belarusian and The New Times

@bajmedia

@bajmedia