“Without us, you wouldn’t know…”: Inside the secrets Belarus wanted buried, until reporters exposed them

Since August 2020, more than 400 journalists have left Belarus due to persecution. Around 30 independent outlets have relocated abroad. They continue working now in some of the harshest conditions in Europe.

Criminal cases are being opened against independent reporters, editorial offices are declared “extremist formations,” and readers, experts, and sources who cooperate with them face prison. Independent media websites are blocked, budgets are minimal. But despite threats, an information blockade, and financial difficulties, Belarusian journalists remain in the profession and continue reporting on what is really happening in Belarus.

To highlight this work, the Belarusian Association of Journalists launched the project “Without us, you wouldn’t know…” It shows what facts, events, and problems in Belarus would have stayed hidden if not for independent media and journalists.

In this article, we present some examples. More about the work and impact of Belarusian independent media can be found on the project’s page “Without us, you wouldn’t know…”

A drone detonated downtown, yet officials said nothing

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in Ukraine, Belarusian independent media have been covering how Belarusian territory is being drawn into military activity and the risks this creates for the population.

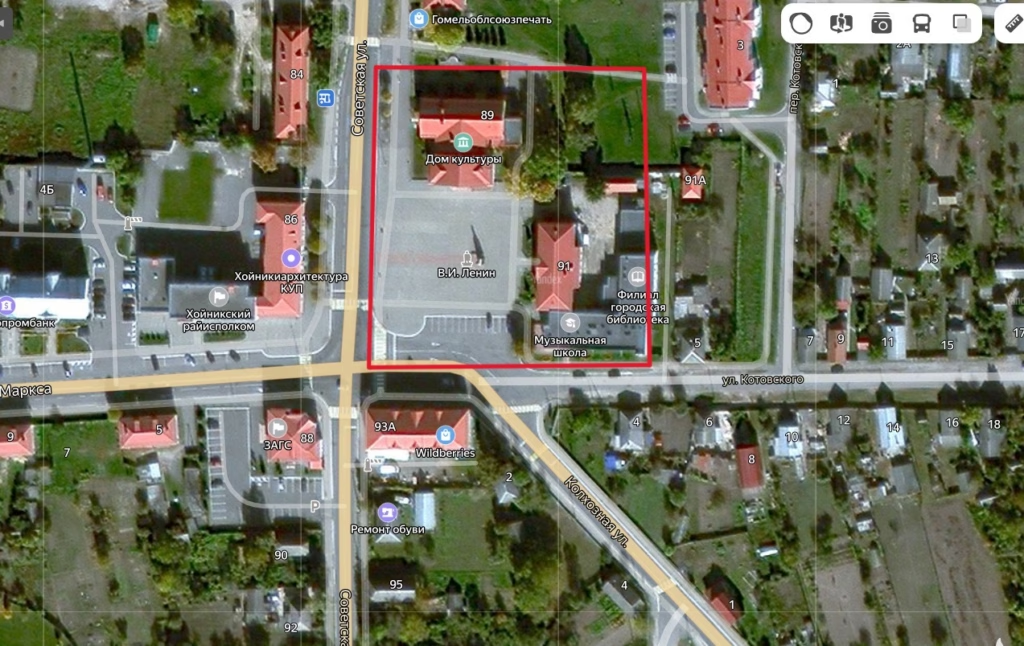

One of the most telling stories was the crash of a Russian drone into a school in the small city of Khoiniki in February 2025. It happened in the city center, among residential buildings, near the local administration, shops, and a library. At night, residents heard an explosion, and some areas were evacuated. But no state institution reported anything, and the local newspaper remained silent.

Journalists have located the likely location of the drone crash. Image: zerkalo.io

The incident was reported by the Belarusian media outlet Zerkalo, created in exile by former journalists of the largest Belarusian news outlel Tut.by after it was destroyed by the authorities. Even from abroad, the editorial team managed to find eyewitnesses.

“We published photos, diagrams, and local reactions. That was an important moment, because without us, people in the region wouldn’t even have known what happened. We showed what an information vacuum looks like. The authorities want people not to ask questions. But how can you pretend to not know when a drone hits your city?” said Zerkalo board member Sasha Pushkina.

A civilian airport turned into a military facility

Thanks to Belarusian independent media, details became known about the use of Belarusian territory at the beginning of the war as a staging area for the attack on Ukraine. Journalists reported on troop movements, airstrikes, and Russian military deployments.

For example, in February 2022 the regional outlet Flagshtok from Homel reported that the local civilian airport had effectively become a military site. Readers, despite the risks, sent photos and videos to the editorial team. This revealed that after the start of the Union Resolve exercises, military flights began arriving at the Homel airport. Public flight trackers didn’t show them, and officially the airport wasn’t listed among the exercise sites.

Il-76 military transport aircraft of the Russian Armed Forces at the Gomel airport on February 25, 2022. Photo: Flagstaff

On February 21, 2022, the airport came fully under Russian military control. Civilian staff and local services were sent on leave. In the days before the war, residents increasingly saw heavy Il-76 transport planes landing and convoys of armored vehicles leaving the airport.

At first this was explained as arms deliveries and the evacuation of the wounded and dead. But on March 20, the Russian Ministry of Defense published a video of Forpost drone strikes on Ukraine. The footage clearly showed the drone taking off and landing specifically at the Homel airport.

Flagshtok continues to report on military activity in the region, documenting Russian drones flying through Belarusian airspace — information the authorities try to conceal. In another border region, Brest, journalists of the local outlet BGmedia also report on similar developments: government military purchases, the construction of a new border post, and more.

Belarusian ‘shamed’ athletes barred from the Olympics

When the Paris Olympics took place in the summer of 2024, journalists from the sports outlet Tribuna tracked which athletes would be allowed to compete. The International Olympic Committee had specific requirements, including that athletes not be part of military structures.

But in Belarus, all athletes are linked in one way or another to the KGB, police, or other similar organizations, explained Tribuna editor-in-chief Maksim Berazinski. Journalists highlighted these issues. As a result, the outlet compiled a “database of the disgrased” of not only Belarusian but also Russian athletes who supported the war.

The IOC did not allow 9 out of 10 Belarusian wrestlers to the 2024 Games. Only Abubakar Khaslanov (pictured) went to Paris. Source: 024.by

From Russia, only 15 athletes went to the Olympics — the lowest number in history. From Belarus, 17 participated.

Journalists were also able to restrict athletes’ involvement in ideological events supporting the war. Previously, this happened often in Russia, but Belarusian athletes also felt free to make such statements.

“When we simply started documenting this and filing everything, loud public support for the war dropped significantly. And I think that’s a very important story in terms of limiting propaganda,” said Tribuna editor-in-chief Maksim Berazinski.

Citizens denied crucial updates on COVID-19 and nuclear plant problems

The Belarusian authorities try to present a “pretty picture” of life in Belarus in their controlled media, where publications are censored and subject to strict ideological control. Meanwhile, the public is deprived of vital information that can directly affect their lives. Such issues only become known after they are exposed by independent media.

For example, Euroradio was among the first to report on a critical food shortage, pricing problems, and the consequences of government regulation. And journalists from Zerkalo revealed that the Belarusian Nuclear Power Plant (BelNPP) had stopped operating.

“It was just a technical fact: the plant had been disconnected from the grid, but all the state media stayed silent,” recalled Sasha Pushkina. “When a nuclear plant shuts down, that’s information society must know. It’s a matter of safety. And when we write about it, that already has an impact. After our report, the Ministry of Energy was forced to admit that BelNPP was indeed offline.”

The most notorious example is how the Belarusian authorities hid information about COVID-19 from their own population. They manipulated infection statistics, and mortality data was fully classified and not published from 2020 to 2025. They stayed silent about shortages of masks, ventilators, and interruptions in hospital operations. All this only became known through independent journalists’ reports.

Belarusian nuclear power plant. Photo: Ministry of Energy

One of the first outlets to cover COVID-19 in Belarus was Vitebski Kurier News, because the epidemic began in Vitsebsk after local shoe factory management returned from a trade fair in Milan. At the time, the outlet became a crucial source of truthful information for both residents and other media.

Belarusian detainees made to work for German lawmaker

Despite pressure and harsh working conditions, Belarusian journalists achieved breakthroughs in investigative reporting. This was possible thanks to new opportunities to collaborate with foreign colleagues, access to databases obtained by the hacker collective Cyber Partisans, and — most importantly — Belarusians themselves, even from within the state system, sharing insider information because they are dissatisfied and want change in the country.

The investigative media outlet Buro was founded in exile and has been operating for only a year and a half. But during that time, it uncovered numerous schemes through which the Belarusian authorities and allied businessmen bypassed European sanctions and even helped supply Russia with Western technology later used to produce weapons.

Buro journalists wrote extensively about hidden businesses and corruption in the Lukashenka family and its inner circle. They also revealed that the Belarusian dictator has an illegitimate daughter. One of their biggest stories was an investigation into the Belarusian Red Cross, which showed the organization spending international grant money on an inflated staff and costly trips.

As a result, the UN announced it would cut ties with the Belarusian Red Cross. In Belarus, the outlet’s website was blocked just 30 minutes after the story was published.

Another high-profile case was an investigation by Reform.news into plantations in Belarus owned by German MP Jörg Dornau of the Alternative for Germany party. His company used forced labor of Belarusian political prisoners, keeping them in inhumane conditions and paying almost nothing.

How regional outlets use insider information to impact local power

It is crucial that the ecosystem of independent Belarusian media in exile has preserved local outlets. For many communities, they are now the only source of independent information about their regions. Importantly, they still manage to influence local authorities.

A clear example is the newsroom of Hrodna.life, which has been operating outside Belarus since 2022. Journalists maintained communication with local residents and monitor moods and events in their city through social media and open sources.

For instance, despite being labeled “extremist,” the outlet managed to force explanations from the authorities when monuments to Belarusian insurgents of the 19th century, who fought against the Russian Empire, suddenly began to be removed in Hrodna. After critical publications by Hrodna.life, local officials carried out housing and road repairs and suspended plans to build a giant flagpole right in the historic center, opposite the church.

Even back when it still operated inside Belarus, the newsroom of Orsha.eu built a strong network for gathering information, and it continues to receive insider tips. For example, the outlet reported on a shocking case when Russian police officers crossed the open border into the Orsha District while under the influence of drugs. One of them killed another right on the highway.

Photo from the scene of the events from the press service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, published after the news on the website orsha.eu

The Belarusian authorities tried to cover up the incident, but Orsha.eu’s publication sparked a wide reaction. People began discussing in comments and on social media the problem of open borders and the threats coming from Russia.

The work of regional journalists is often picked up by nationwide media.

“It’s like small and big rivers. Without the smaller ones, it becomes harder for the big resources to function. Some information would never reach readers at all,” explained BGmedia editor-in-chief Viktar Marchuk.

For instance, BGmedia journalists uncovered important details about the construction of a toxic plant in Brest and the sharp decline in the working-age population in the region.

Previously, Brest journalists wrote a lot about residents’ protests against the construction of a battery plant — because of this, their editorial office was deprived of its office. Now BGmedia is not letting information about a new toxic enterprise in Brest remain silent. Archive photo: BGmedia

But for small local outlets in exile, securing funding and attracting foreign donors is the hardest challenge. Right now, both BGmedia and Vitebski Kurier News have launched fundraising campaigns just to cover staff salaries, as their situation has become critical.

Belarusian-language content against the “Russian world”

Inside Belarus, a policy of Russianization is being enforced: the Belarusian language is hardly used, and national culture, traditions, and history are being pushed out of the public space. In this context, independent Belarusian media in exile play another vital role: preserving national consciousness and identity. They do so through stories that reflect a Belarus-centered perspective on history and current events. Even the mere fact of publishing in the Belarusian language becomes significant.

One such outlet is PALATNO, which collects fascinating facts about Belarusian language and culture, offers engaging stories about history, and works extensively with archives and memoirs. Did you know, for example, that Stanislau Albrecht Radzivil, an aristocrat from a famous Western Belarusian noble family, helped John Kennedy become president? Or that the first president of Hawaii was Belarusian?

One of the heroines of the podcast “Land of Freedom” — little Rosalind sailed with her mother from Belarus to America on a ship for 10 days. Image: PALATNO

Any Belarusian-language content — and especially high-quality content — contributes to preserving Belarusianness and distancing from the “Russian world,” believes PALATNO editor Zoya Khrutskaya.

“I am convinced that we need many more diverse projects in Belarusian. Expanding the Belarusian-language space is one of the keys to Belarus’s independence and sovereignty.”

@bajmedia

@bajmedia